I’ve been using this Levenberg-Marquardt library for some time now mostly as a black box. It’s OK performance wise and it never came up at the top of the profiler. This was mostly due to my objective function being extremely slow.

After spending some time optimizing the objective function’s code, the library started taking more and more of the total execution time. So it was time to take a look inside to see if I can do something about it.

In no particular order below are the major changes I tried.

Calculate J^T instead of J

The library uses row-major matrices. When fitting an objective function with M parameters to N experimental data points, the Jacobian is NxM (N rows by M columns). Usually (at least in my case) the number of data points N is 1 to 2 orders of magnitude greater than the number of parameters M. E.g. usually N is in the range [512, 2048] and M is in the range [3, 10].

Ignoring how the Jacobian is calculated for a moment, the first piece of code that uses it calculates J^T*J. Below is the comment from that particular function.

/* blocked multiplication of the transpose of the nxm matrix a with itself (i.e. a^T a)

* using a block size of bsize. The product is returned in b.

* Since a^T a is symmetric, its computation can be sped up by computing only its

* upper triangular part and copying it to the lower part.

*

* More details on blocking can be found at

* http://www-2.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs/academic/class/15213-f02/www/R07/section_a/Recitation07-SectionA.pdf

*/

void LEVMAR_TRANS_MAT_MAT_MULT(LM_REAL *a, LM_REAL *b, int n, int m)

{

// Refer to the original misc_core.c for the function body.

}

The default block size is 32. My first thought when I looked at that comment was “how much does blocking help when the matrix is e.g. 2048x5?”. So I rewrote the code to not use blocking at all (the result is the same as setting the block size to a very large value, but avoids the extra bookkeeping) and unrolled the loop 4 times using 4 independent sums. Below is my version:

void lm_AT_mul_A_ref(const float* a, float* b, uint32_t n, uint32_t m)

{

float* b_ptr = b;

for (uint32_t iParam = 0; iParam < m; ++iParam) {

for (uint32_t jParam = iParam; jParam < m; ++jParam) {

float sum0 = 0.0f;

float sum1 = 0.0f;

float sum2 = 0.0f;

float sum3 = 0.0f;

const float* a0_ptr = &a[m * 0];

const float* a1_ptr = &a[m * 1];

const float* a2_ptr = &a[m * 2];

const float* a3_ptr = &a[m * 3];

uint32_t remaining = n;

while (remaining >= 4) {

sum0 += a0_ptr[iParam] * a0_ptr[jParam];

sum1 += a1_ptr[iParam] * a1_ptr[jParam];

sum2 += a2_ptr[iParam] * a2_ptr[jParam];

sum3 += a3_ptr[iParam] * a3_ptr[jParam];

a0_ptr += m * 4;

a1_ptr += m * 4;

a2_ptr += m * 4;

a3_ptr += m * 4;

remaining -= 4;

}

float sum = sum0 + sum1 + sum2 + sum3;

switch (remaining) {

case 3:

sum += a0_ptr[iParam] * a0_ptr[jParam];

a0_ptr += m;

case 2:

sum += a0_ptr[iParam] * a0_ptr[jParam];

a0_ptr += m;

case 1:

sum += a0_ptr[iParam] * a0_ptr[jParam];

a0_ptr += m;

}

b_ptr[jParam] = sum;

}

b_ptr += m;

}

b_ptr = b;

for (uint32_t iParam = 0; iParam < m; ++iParam) {

const float* bj_ptr = &b[iParam];

for (uint32_t jParam = 0; jParam < iParam; ++jParam) {

b_ptr[jParam] = *bj_ptr;

bj_ptr += m;

}

b_ptr += m;

}

}

Too bad this code cannot be vectorized because it jumps m elements in each iteration. Maybe if a was J^T and instead of a^T * a the function calculated a * a^T it could be much faster.

Before commiting to such a big change lets look at the next and final piece of code which uses the Jacobian. As far as I understand it updates the Jacobian when a better estimation for the parameters is found, in order to avoid reevaluating the objective function M times. To be honest, I don’t fully understand the math.

/* update jac */

for (i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

for (l = 0, tmp = 0.0; l < m; ++l)

tmp += jac[i * m + l] * Dp[l]; /* (J * Dp)[i] */

tmp = (wrk[i] - hx[i] - tmp) / Dp_L2; /* (f(p+dp)[i] - f(p)[i] - (J * Dp)[i])/(dp^T*dp) */

for (j = 0; j < m; ++j)

jac[i * m + j] += tmp * Dp[j];

}

The major issue with this piece of code (which btw takes the majority of the minimization function’s self time) is that the outer loop is way larger (N) than the inner loops. It doesn’t make sense attempting to vectorize the inner loops because M is compareable to the vector width (4 for SSE, 8 for AVX). The only way to have a chance at vectorization is to reorder the loops. This requires a temporary vector for holding J*Dp. Something like the following:

void lm_updateJacobian_ref(float* jac, const float* dp, const float* f_pdp, const float* f_p, uint32_t n, uint32_t m, float dp_L2, float* jac_dp)

{

memset(jac_dp, 0, sizeof(float) * n);

for (uint32_t iParam = 0; iParam < m; ++iParam) {

for (uint32_t iSample = 0; iSample < n; ++iSample) {

// (J * Dp)[i]

jac_dp[iSample] += jac[iSample * m + iParam] * dp[iParam];

}

}

const float inv_dp_L2 = 1.0f / dp_L2;

for (uint32_t iSample = 0; iSample < n; ++iSample) {

// (f(p + dp)[i] - f(p)[i] - (J * Dp)[i]) / (dp^T * dp)

jac_dp[iSample] = (f_pdp[iSample] - f_p[iSample] - jac_dp[iSample]) * inv_dp_L2;

}

for (uint32_t iParam = 0; iParam < m; ++iParam) {

for (uint32_t iSample = 0; iSample < n; ++iSample) {

jac[iSample * m + iParam] += jac_dp[iSample] * dp[iParam];

}

}

}

Doing things this way, we end up in the same situation as lm_AT_mul_A_ref. The inner loops could be easily vectorized if instead of J we had J^T. The question is whether it makes sense to keep calculating J and transposing it or calculate J^T directly? Let’s look at the code that calculates J:

/* forward finite difference approximation to the Jacobian of func */

void LEVMAR_FDIF_FORW_JAC_APPROX(

void (*func)(LM_REAL *p, LM_REAL *hx, int m, int n, void *adata), /* function to differentiate */

LM_REAL *p, /* I: current parameter estimate, mx1 */

LM_REAL *hx, /* I: func evaluated at p, i.e. hx=func(p), nx1 */

LM_REAL *hxx, /* W/O: work array for evaluating func(p+delta), nx1 */

LM_REAL delta, /* increment for computing the Jacobian */

LM_REAL *jac, /* O: array for storing approximated Jacobian, nxm */

int m,

int n,

void *adata)

{

int i, j;

LM_REAL tmp;

LM_REAL d;

for(j = 0; j < m; ++j){

/* determine d=max(1E-04*|p[j]|, delta), see HZ */

d = LM_CNST(1E-04) * p[j]; // force evaluation

d = FABS(d);

if (d < delta)

d = delta;

tmp = p[j];

p[j] += d;

(*func)(p, hxx, m, n, adata);

p[j] = tmp; /* restore */

d = LM_CNST(1.0)/d; /* invert so that divisions can be carried out faster as multiplications */

for(i = 0; i < n; ++i){

jac[i * m + j] = (hxx[i] - hx[i]) * d;

}

}

}

In this case the outer loop is over M which is the smaller dimension. That’s good news. The problem is that the inner loop skips ‘m’ elements in each iteration. I think it’s obvious that calculating J^T instead of J can again make the inner loop vectorizable.

If all the above changes are made, the code should never calculate or use the Jacobian at all but instead calculate and use its transpose J^T.

Below is my version of the code. First the function that calculates J^T

void lm_fdiffJacTForward_ref(lmObjectiveFunctionCallbackf objFunc, float* p, const float* hx, float* hxx, float delta, float* jacT, uint32_t m, uint32_t n, void* adata)

{

for (uint32_t iParam = 0; iParam < m; ++iParam) {

// determine d=max(1E-04*|p[j]|, delta), see HZ

float d = 1e-4f * p[iParam]; // force evaluation

d = jx_absf(d);

if (d < delta) {

d = delta;

}

float tmp = p[iParam];

p[iParam] += d;

objFunc(hxx, n, p, m, adata);

p[iParam] = tmp; // restore

d = 1.0f / d; // invert so that divisions can be carried out faster as multiplications

float* jacT_ptr = &jacT[iParam * n];

for (uint32_t iSample = 0; iSample < n; ++iSample) {

jacT_ptr[iSample] = (hxx[iSample] - hx[iSample]) * d;

}

}

}

Next is the function that calculates J^T * J by using J^T as the input matrix.

void lm_A_mul_AT_ref(const float* a, float* b, uint32_t m, uint32_t n)

{

float* b_ptr = b;

for (uint32_t iParam = 0; iParam < m; ++iParam) {

for (uint32_t jParam = iParam; jParam < m; ++jParam) {

float sum0 = 0.0f;

float sum1 = 0.0f;

float sum2 = 0.0f;

float sum3 = 0.0f;

const float* i_vec_ptr = &a[iParam * n];

const float* j_vec_ptr = &a[jParam * n];

uint32_t remaining = n;

while (remaining >= 4) {

sum0 += i_vec_ptr[0] * j_vec_ptr[0];

sum1 += i_vec_ptr[1] * j_vec_ptr[1];

sum2 += i_vec_ptr[2] * j_vec_ptr[2];

sum3 += i_vec_ptr[3] * j_vec_ptr[3];

i_vec_ptr += 4;

j_vec_ptr += 4;

remaining -= 4;

}

float sum = sum0 + sum1 + sum2 + sum3;

switch (remaining) {

case 3:

sum += *i_vec_ptr++ * *j_vec_ptr++;

case 2:

sum += *i_vec_ptr++ * *j_vec_ptr++;

case 1:

sum += *i_vec_ptr++ * *j_vec_ptr++;

}

b_ptr[jParam] = sum;

}

b_ptr += m;

}

b_ptr = b;

for (uint32_t iParam = 0; iParam < m; ++iParam) {

const float* bj_ptr = &b[iParam];

for (uint32_t jParam = 0; jParam < iParam; ++jParam) {

b_ptr[jParam] = *bj_ptr;

bj_ptr += m;

}

b_ptr += m;

}

}

And finally the function that updates J^T when a better estimate is found.

void lm_updateJacobianTranspose_ref(float* jacT, const float* dp, const float* f_pdp, const float* f_p, uint32_t n, uint32_t m, float dp_L2, float* jac_dp)

{

memset(jac_dp, 0, sizeof(float) * n);

for (uint32_t iParam = 0; iParam < m; ++iParam) {

const float* jacT_ptr = &jacT[iParam * n];

const float dp_i = dp[iParam];

for (uint32_t iSample = 0; iSample < n; ++iSample) {

// (J * Dp)[i]

jac_dp[iSample] += jacT_ptr[iSample] * dp_i;

}

}

const float inv_dp_L2 = 1.0f / dp_L2;

for (uint32_t iSample = 0; iSample < n; ++iSample) {

// (f(p + dp)[i] - f(p)[i] - (J * Dp)[i]) / (dp^T * dp)

jac_dp[iSample] = (f_pdp[iSample] - f_p[iSample] - jac_dp[iSample]) * inv_dp_L2;

}

for (uint32_t iParam = 0; iParam < m; ++iParam) {

float* jacT_ptr = &jacT[iParam * n];

const float dp_i = dp[iParam];

for (uint32_t iSample = 0; iSample < n; ++iSample) {

jacT_ptr[iSample] += jac_dp[iSample] * dp_i;

}

}

}

All inner loops in the above functions are over the largest dimension of the system (N, the number of experimental data points) and are easily vectorizable using either SSE/AVX intrinsics directly or your favorite SIMD abstraction library.

J^T * e

Since I now have J^T, the code that calculates J^T * e, using J and e (e is the error vector):

/* cache efficient computation of J^T e */

for(i=0; i<m; ++i)

jacTe[i]=0.0;

for(i=0; i<n; ++i){

register LM_REAL *jacrow;

for(l=0, jacrow=jac+i*m, tmp=e[i]; l<m; ++l)

jacTe[l]+=jacrow[l]*tmp;

}

can be replaced by a matrix-vector multiply

void lm_A_mul_v_ref(const float* a, const float* v, float* res, uint32_t m, uint32_t n)

{

const float* a_ptr = a;

for (uint32_t iParam = 0; iParam < m; ++iParam) {

float sum = 0.0f;

for (uint32_t iSample = 0; iSample < n; ++iSample) {

sum += *a_ptr++ * v[iSample];

}

res[iParam] = sum;

}

}

which is again easily vectorizable.

L2 norm and error vector

The last part which can be easily vectorized is the function that calculates the error vector and its squared L2 norm.

/* Compute e=x-y for two n-vectors x and y and return the squared L2 norm of e.

* e can coincide with either x or y; x can be NULL, in which case it is assumed

* to be equal to the zero vector.

* Uses loop unrolling and blocking to reduce bookkeeping overhead & pipeline

* stalls and increase instruction-level parallelism; see http://www.abarnett.demon.co.uk/tutorial.html

*/

LM_REAL LEVMAR_L2NRMXMY(LM_REAL *e, const LM_REAL *x, const LM_REAL *y, int n)

{

// Check misc_core.c from the original sources.

}

I’m using the exact same code as my reference implementation without the part where x can be NULL because it never is in my case. So nothing to show in this case.

Results

The size of the problem in all benchmarks and profiles below is M = 3 and N = 1224. The minimization function is executed 378 (3 * 18 * 7) times (i.e. different initial estimates). This is because my error function has a lot of local minima and I’m looking for the global minimum. The whole process is repeated 10 times.

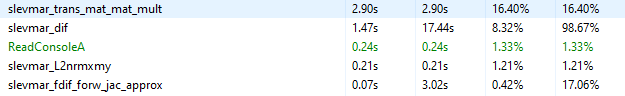

First a profile snapshot using the original library code.

slevmar_dif spents 0.46s out of its own 1.47s to calculate J^T * e and 1.00s to update J. The remaining 0.01s is the rest of the function.

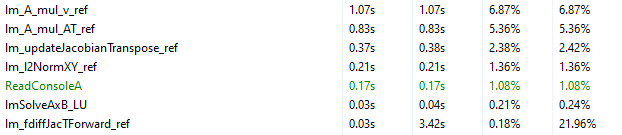

Now a profile using the reference implementation of all the functions I discussed above.

In this case J^T * e (lm_A_mul_v_ref) takes more time than before (1.07s vs 0.46s). But J^T * J time (lm_A_mul_AT_ref) was reduced from 2.90s to 0.83s and the Jacobian update time (lm_updateJacobianTranspose_ref) was reduced from 1.00s to 0.37s. The L2 norm function is exactly the same because as I mentioned above my reference implementation is exactly the same as the library’s version. Finally a minor win when calculating J^T (lm_fdiffJacTForward_ref) with a reduction from 0.07s to 0.03s.

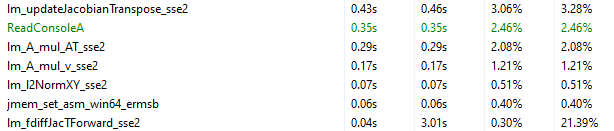

Next a profile using the SSE2 optimized versions of the functions.

For some reason lm_updateJacobianTranspose_sse2 is slower than the reference version (0.43s vs 0.37s) but still faster than the original code. J^T * J time was again reduced to 0.29s and J^T * e is now faster than the original code (0.17s vs 0.46s). Finally the L2 norm function time (lm_l2NormXY_sse2) was reduced from 0.21s to 0.07s.

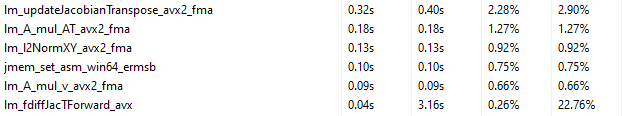

Finally a profile using the AVX2+FMA optimized versions of the functions

Some further improvements in this case and a regression. lm_updateJacobianTranspose_avx2_fma is 0.11s faster, lm_A_mul_AT_avx2_fma is also 0.11s faster but the lm_l2NormXY_avx2_fma is 0.06s slower. Overall not a big win for AVX2. I’ll have to investigate further whether any more gains can be obtained from this version.

Below is a table comparing the various versions of the code. Times are per minimization iteration in microseconds.

| Version |

Min |

Average |

Max |

StdDev |

Minimum Error |

Iterations |

Objective Function Evaluations |

| original |

27.893 |

28.101 |

29.204 |

0.391 |

7.720187902e-01 |

54179 |

71769 |

| reference |

24.467 |

24.697 |

25.273 |

0.307 |

7.720187306e-01 |

54433 |

72109 |

| SSE2 |

22.186 |

22.446 |

22.951 |

0.233 |

7.720186710e-01 |

54247 |

71905 |

| AVX2+FMA |

22.504 |

22.569 |

22.655 |

0.047 |

7.720184922e-01 |

54415 |

72098 |

One last remark. The total objective function evaluations and the number of iterations depend on the intermediate results. Since the various versions do not calculate the exact same thing, some minor differences are expected. All benchmarks were executed with the exact same minimization options.